This is intended to serve as a journal entry for me (it is not for any academic purpose); it is my first ever exploration of what ‘hate’ and ‘evil’ mean—it is thus, I must admit, not rigorous. But if anyone finds it interesting, that would, of course, make me happy. 🙂

Record-keeping, 18-22 March 2020

Section I: the spark of thought

From a careless exchange on our feelings for cats, my friend and I began a discussion on ‘hate‘ a few days ago. One of my other friends claimed to hate cats, but that one is adorable… My friend’s reaction to this claim was of a strong aversion, for [my analysis is that] to him it betrayed an underlying lack of finesse in appreciating what ‘hate’ entails.

In my regular life, I use the term ‘hate’ very freely in comparison to him; I frequently say things like “oh, I hate that [e.g. an instance of hypocrisy].” Thus, my immediate reaction to his response was one of great curiosity, for I had not previously thought hard about how the word ‘hate’ is used nor had found its use in colloquial English problematic: exaggerated, maybe, but not reprehensible.

It is possible, I thought, that the term ‘hate’ has a thicker meaning in colloquial German (he is a native German speaker with non-native English) than in colloquial English (I am a native English speaker). The closest term to ‘hate’ in Japanese (I am a native Japanese speaker) 憎しみ, nikushimi, certainly carries with it an extremely negative and dark meaning; indeed, I have never personally used it. In Mandarin Chinese (with which I am reasonably well-acquainted) 讨厌, tao3yan4, is not as but similarly very strong from what I understand of it. But, he relayed, many Germans often use hassen carelessly; my personal experience from the last year and a half living in München also supports his empirical claim.

He told me that to him, ‘hate’ is something [very dark and] serious. For example, ‘to hate X’ is ‘to want to see X die’ or ‘to want to see X not exist’ in a way that riles up one’s feelings intensely. It is considerably more intense than simply not liking X. No wonder, I thought, others’ frequent use of the term seemed overdramatic and frustrated him.

Given my interest in contemporary theory of action, the way I have conceptualized ‘hate’ in recent years is something along the lines of: ‘a negative feeling or attitude towards an object that provides motivational force in favor of taking a certain course of action towards that object’. If a Marxist ‘hates’ the suffering of the poor, overworked polloi, then they find themselves motivated to take action to get rid of the suffering of hoi polloi. Setting aside my distaste for communism, I have thought that ‘hate’ isn’t necessarily bad.

I wanted to understand his thoughts. Perhaps his conception of ‘hate’ is so strong because, I suggested to him, it might be closely connected to the notion of ‘evil’ with which Western ethical frameworks are often heavily imbued. To me, that would have explained why it seems so bad to him. Things then got very interesting for me, for he responded with a view I had never before considered regarding the relationship between ‘hate’ and ‘evil’. Below, I organize and present his intuitions, interposing implied statements, as well as I am able:

‘Hate’ and ‘evil’ are, in a certain way, mutually exclusive. In the following way: ‘Evil’ is manifest in an agent or an action when someone does really horrible things to some object (animals, people, society, and things more generally) without feeling hate. ‘Hate’ entails the capacity to strongly feel. ‘Evil’ entails that capacity be absent.

If agent A ‘hates’ object X and does something horrible to X, then we have an account with strong explanatory force for as to why A did what they did. Assume that we humans all understand what it is to ‘hate’ something; we can understand why A did what they did. In contrast, it is in the nature of ‘evil’ that we cannot understand it or an act of it, i.e. an act of ‘evil’ is incomprehensible.

Furthermore, ‘hate’ is something that can be instrumentalized and be made common, for example, by an excellent use of propaganda. On the other hand, true ‘evil’ is rare.

An example for ‘evil’, he thought, could be Dr. Josef Mengele and his twin-children experiments in Auschwitz. These experiments notoriously could not be defended in the Doctors’ Trial in Nuremberg 1946-7 with the clause that they were done for the sake of military needs; his experiments had no foreseeable benefit for the Nazi war effort. Other Nazis may have been full of ‘hate’ for Jews, but Dr. Josef Mengele was ‘evil’.

The basic idea (this is admittedly a complex example to fully spell out, but I would like to keep my friend’s example): Dr. Mengele lacks reasons that we can understand for doing the horrible things he did. Dr. Mengele was among the few Nazis who acted in an ‘evil’ way, while the others were unjustifiably, but comprehensibly acting out of ‘hate’.

Another one of my dear friends Luise (a law student) pointed out to me how interesting this is especially in light of a particular criterium in the German criminal code that has been in effect since 1872 (§ 211 Abs. 2 Gr. 1 Var. 4 StGB). One criterium for murder is “Niedrige Beweggründe”, which directly translates into English as “base motives”. This criterium is met when the motives for the crime is considered morally base, despicable… and, (interestingly!) definitionally, ‘incomprehensible’.

I had the following immediate musings in response to my friend’s idea:

0) it seems that he is thinking about moral evil, not natural evil (e.g. natural disasters) so I don’t have to dive into the Epicurean complications of the Problem of Evil.

1) his conception of a person who is ‘evil’ seems to me like that of a full-fledged psychopath. The ‘evil’ person is not only on the psychopath spectrum (according to the DSM-5, you need only 30 of 40 total points on the 20 criteria [0-2 pts/criterium] to be clinically diagnosed as one), but also an instantiation of the concept of a psychopath. I would recommend reading other sources on Dr. Josef Mengele, he is fascinatingly terrible.

2) this conception of ‘evil’ resonates strongly with my understanding of the Christian notion of evil. In trying to find another conception that would be a better fit, I accidentally read the entire Wikipedia page for ‘evil’; I found none. I further called one of my best friends, Hope Kean (neuroscience PhD student), for some hours to discuss the Christian notion of ‘evil’ because she is brilliant and very knowledgeable about Christian theology.

3) this is in stark contrast to what I understand of the now commonly understood idea behind the phrase: ‘the banality of evil’. And probably thus, the claim that the presence of ‘hate’ precludes ‘evil’ seems prima facie incorrect to me.

Section II: better and worse ‘evil’s in Christian theology: e.g., Dante’s Inferno

In this section I expand on (2). In Christian theology, ‘evil’ is most basically defined as the total ‘lack of good’. (This is very Platonic!) Since I am not an expert on Christian thought, I fear I will misrepresent Christian, specifically Catholic (more specifically Dominican theology)… and thus,

were I to put this concept instead in psychological terms, an ‘evil’ person is one who totally lacks orientation towards what is good and bad when they are engaging in deliberation for whether to do action X or to not do X. I find this idea similar to the ‘evil’ person my friend spelled out. Below is my train of thought as to why:

Many scholars (e.g., Aristotle) think that a certain subset of emotions track the goodness and badness (or justice/injustice) of situations. [Note: My formulation of the previous sentence is influenced greatly by conversations the past few months with my friend Andrew Romanowski, who studies emotion in Aristotle.] For example, if I see agent A torturing children, I ought to feel anger and disgust towards A and A’s conduct, because regardless of my opinions on child torture, feeling anger and disgust is the appropriate emotional response to the sight of torturing children.

This conceptually presupposes that there is an appropriate emotional response to be had for (at least a certain subset of) sensory experiences. If this is right, the thought continues: one not having the appropriate emotional response to their experiences indicates that one’s orientation towards what is good and bad has gone out of whack for some reason or other (e.g., experiencing abuse as a child. see Gideon Rosen’s work on moral culpability: I—Culpability and Duress: A Case Study and IV—Culpability and Ignorance).

Since we non-psychopaths are all to varying degrees oriented towards what is good–certainly oriented towards what appears good to us and for the most part try to make appearances align with our best guess of reality—when we are exposed to someone or someone’s action that exhibits a total lack of orientation towards what is good, we find it difficult to understand. In extreme cases, we find them and their actions incomprehensible. They and their actions seem ‘evil’ to us.

Dr. Josef Mengele seems ‘evil’ to us, the thought goes, because he carried out the experiments for not only no justifying reasons, but also no explanatory reasons, and—my friend’s thought I think is—without the appropriate emotional response warranted by beholding his own actions. He famously took great pleasure in his work. He evaded the Trials, fled to South America and died there drowning upon suffering a stroke.

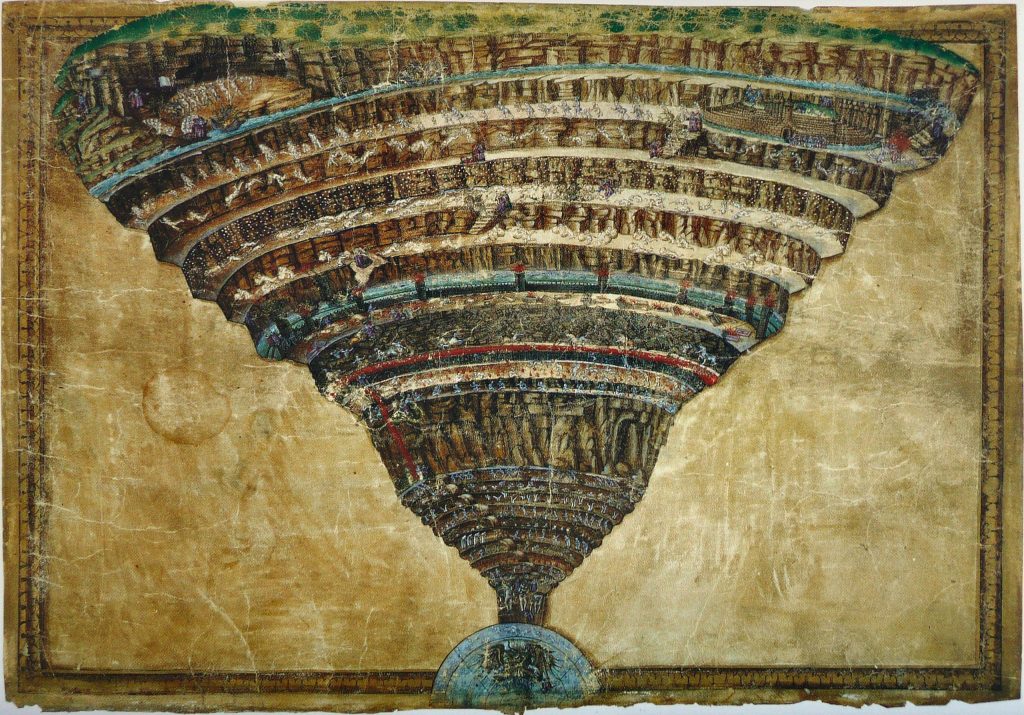

Hope and I discussed (Hope made the connection!) the similarities between my friend’s thoughts on ‘evil’ and the deeper circles of hell in Dante’s Inferno. It was true to both our impressions from having read it years ago that the earlier rings of hell are for people who partook in ‘evils’ or ‘sins’ that were motivated-by-feelings, and I think the thought is (assumption: feeling feelings is part of human nature): thus, more readily comprehensible. For example, the rings of lust and gluttony. The deeper and ‘worse’ rings of hell have a more intellectual flavor to the ‘evils’ committed by their inhabitants, arguably unrelated to ephemeral pathê. These inhabitants also look less recognizably human as Dante describes what he sees.

Thus after our phone call I reread the entire Inferno (it was so good, I had to force myself to go to sleep! hadn’t opened it for 5 years…) to see if our distant memories of it and our impressions were well-founded. Below are some excerpts I found particularly illuminating (English translation by Robert and Jean Hollander):

Note: Dante Alghieri, 1265-1321 was certainly well-acquainted with the works of ancient scholars (Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, Democritus, Diogenes, Anaxagoras, Thales, Empedocles, Heraclitus, Zeno, Dioscorides, Cicero, Seneca, Euclid, Ptolemy, Hippocrates, Galen) and their Arabic reception (Avicenna, Averroes). This is clear from reading Inferno Canto IV 130-144; every single one of the scholars I just listed are mentioned there. It is thus important/helpful to keep ancient theories in mind while engaging with his work.

In particular, if there is one thing I could claim to be confident about in this entire post, it is the following: Dante’s understanding of the world is heavily influenced by his understanding of Aristotle. There is plenty of evidence to support this claim, but here is the most direct evidence from the Inferno:

Canto IV 131-135: character Dante speaks of Aristotle as “the master of those who know, // sitting among his philosophic kindred. // Eyes trained on him, all show him honor. // In front of all the rest and nearest him // I saw Socrates and Plato.”

Canto XI 79-84 and 97-105: character Dante explicitly refers to the Nicomachean Ethics and the Physics with great reverence.

I mention these notes on his influences now because my following notes are heavily informed by this background assumption.

Canto II 88-90: ‘ “We should fear those things alone // that have the power to harm. // Nothing else is frightening.

Temer si dee di sole quelle cose // c’hanno potenza di fare altrui male; // de l’altre no, ché non son paurose.

In this passage, Virgil appeases Dante’s fears of entering hell by relaying Beatrice’s words on why she is unafraid of going down to hell from her rightful place in heaven.

This passage does well to show the underlying assumption in Christian teaching that there are (at least some) things that are objective. Beatrice speaks of things that are objectively frightening. There are things we fear, then there are objectively frightening things that we should fear, and these are conceptually separable. Thus, there are objectively appropriate occasions to feel fear and objectively inappropriate occasions to feel fear. I note that this passage does not entail that all emotions should work according to objective measures in Christian doctrine, but at least some do.

Canto III 16-18: ‘We have come to where I said // you would see the miserable sinners // who have lost the good of the intellect.’

[Noi siam venuti al loco ov’i’ t’ho detto // che tu vedrai le genti dolorose // c’hanno perduto il ben de l’intelletto.]

This passage occurs in the context of Virgil and Dante entering the gates of hell. Upon seeing the gate’s inscription, Dante claims to not understand it; Virgil explains.

This passage provides us the criterium by which people are sent to hell. Hell consists of sinners, which is basically synonymous with: those who engaged in some category of ‘evil’ acts during their lives and thus ‘lost the good of the intellect’.

It is simply undeniable that neo-Platonism greatly influenced Christian theology.* Here are some Platonic or neo-Platonic ideas I am aware of that may clarify what is meant by ‘lost the good of the intellect’:

0) The Good == the One. This is Plotinus’ interpretation of Plato. This reading finds support in the Platonic dialogues Timaeus and Philebus**.

1) The previous equivalence leads the way to the development of the transcendentals in neo-Platonism from Plotinus to Albert the Great and Saint Thomas Aquinas, the last of which is contemporary to Dante. There are many variations, but I will just pick the version I am more familiar with:

Being == Good == Truth == Beauty

What does this mean? Basically, from various parts of Plato’s work, e.g. the sun analogy in Republic Book VI, we understand the Good as that which provides existence (i.e. being) to all things. The existence of any particular object in the world X metaphysically depends on the existence that the Good gives it. Insofar as X has ‘faults’, is temporary, etc. X is lacking in its “participation” in the Good, which is perfect, everlasting, etc.

The immediate connection that comes to mind: the Judeo-Christian God bears a close resemblance to the Good***, albeit anthropomorphized (but the anthropomorphic portrayal of the creator of everything is unsurprising even for a Platonist, let alone a neo-Platonist, given what we read of the demiurge in the creation story of the Timaeus).

So we have something along the lines of: God is the One perfect thing that exists, and is equivalent in meaning to Goodness, Truth and Beauty. This is a gross over-simplification, but it will do for my purposes in this journal entry.

With this, it is easy, I think, to see why in Christian theology, ‘evil’ is basically defined as the total ‘lack of good’, as we said in the beginning of this section. The ‘evil’ of turning away from God consists in the denial or turning away from all that is good, true, beautiful, etc.

2) Intellect (or its Attic Greek origin νοῦς with which I am more comfortable), or at least its ideal state consists in a cognitive grasp of the things that are subject to the criterion of truth.

Aristotle and Plato both, and thus many others, think that X’s capacity to do something Y corresponds to the appropriateness of X doing Y (e.g., the ἔργον argument in EN Book I.7 or Plato’s discussion of δυνάμεις in Republic Book V).

Thus, I think we can understand the intellect in this passage as something that should be used for grasping truth. An account for intellect like this which informs my understanding of Dante’s passage is explicitly available in Aristotle, e.g., EN Book VI.6 1141a2-5: εἰ δὴ οἷς ἀληθεύομεν καὶ μηδέποτε διαψευδόμεθα περὶ τὰ μὴ ἐνδεχόμενα ἢ καὶ ἐνδεχόμενα ἄλλως ἔχειν, ἐπιστήμη καὶ φρόνησίς ἐστι καὶ σοφία καὶ νοῦς.

With these immediate thoughts in mind, I understand the criterium in this passage of entering hell, to be of those “who have lost the good of the intellect” as something like the following: people who lived without using their intellect / mind (another common translation of νοῦς) for the purpose of grasping truth, the task in which it should engage. The good of the intellect consists in its use for grasping truth. That they have lost this good means that they have deviated from the correct orientation towards what is ‘true’, e.g., God. And further, by doing so, they in their lives failed to orient themselves towards what is good, true, beautiful, etc.

The above is my quick sketch of the musings that came to my mind while reading this passage; I do not consider myself to have argued for this interpretation.

* Thank you to my professor, Peter Adamson, an expert in Neo-Platonic and the Arabic reception of Ancient Greek thought, for sharing and explaining many of these things more robustly (and more accurately) to me. For my background knowledge of Plato and neo-Platonism I am also greatly indebted to the teachings of Professors Benjamin Morison and Hendrik Lorenz from 2014.

** I am grateful to my wonderful friend and scholar Merrick Anderson for pointing out the Philebus to me as an example of where this Platonic idea is prominent.

*** This thought was first mentioned to me by Professor Hendrik Lorenz in 2017.

Canto VI 91-93 With that his clear eyes lost their focus. // He gazed at me until his head drooped down. // Then he fell back among his blind companions.

Li diritti occhi torse allora in biechi; // guardommi un poco e poi chinò la testa: // cadde con essa a par de li altri ciechi.

This passage comes immediately after Ciacco, who is in hell for the sin of gluttony, finishes speaking to Dante. Dante narrates.

The metaphor of ‘sight’ is a common and powerful one since antiquity. After his exchange with his former friend Dante, Ciacco’s eyes lose their focus and he falls back among his blind companions. In both Platonic/neo-Platonic and Aristotelian/Peripatetic thought, the learning that occurs in one’s mind/soul is conceptualized as a ‘turning’ of the eye of the soul towards truth and goodness. This passage made me think that people who take part in ‘evil’ things are those who have lost sight of what is good. Indeed, those in the third circle are blind.

Canto VII 52-54 And he to me: ‘You muster an empty thought. // The undiscerning life that made them foul // now makes them hard to recognize.

Ed elli a me: “Vano pensiero aduni: // la sconoscente vita che i fé sozzi, // ad ogne conoscenza or li fa bruni.

This passage occurs in the fourth circle (greed/avarice/prodigality). Dante is confused about why he cannot recognize anyone there. Virgil explains.

Note on the phrase ‘the undiscerning life’. These sinners, if what we have from before is right, are in hell because they turned their minds away from God in life, and thus also away from what is true and good. Earlier, I proposed that the conception of the ‘evil’ person we are working with is the one whose orientation towards what is good and bad is somehow out of whack.

Perhaps the ‘undiscerning life’ in this passage is similar. My train of thought is as follows: the person who does not discern what is good from what is bad in deciding what to do has turned away from the acquisition of the correct orientation towards what is good.

Put ‘moral luck’ and those complications aside (see the work of Bernard Williams & Thomas Nagel), acquiring the correct orientation requires a great effort of, as earlier suggested, the intellect. Their lack of engagement with the correct way of being human in life corresponds to their lack of being recognizably human in death.

This circle of hell is where, as per Hope and my thoughts, the ‘evils’ committed start to become more intellectual in flavor. It is here where the sinners start to become unidentifiable as human, and their sins, I would argue, start to become more or less unrelatable to a normal person. As we shall see, there are also sins that are simply incomprehensible.

To note, the ‘undiscerning life’ also immediately made me think of the Apology’s ὁ… ἀνεξέταστος βίος οὐ βιωτὸς ἀνθρώπῳ (38a), or “the unexamined life is not worth living”. This is interesting because ‘evil’ is discussed in the Apology. For reasons of time, I leave this cliché matter for another occasion.

There are various passages in the remaining Cantos that I think quite strongly suggest the intellectual natures of the evils in the deeper circles OR the non-human-ness of those there. Below I quote a few that I thought were particularly suggestive:

(1) The following passage occurs in the sixth circle, where all heretics go.

Canto X 13-15 ‘Here Epicurus and all his followers, // who hold the soul dies with the body, // have their burial place.

Epicureans’ eternal punishment is for having made a false claim, that ‘the soul dies with the body’, i.e., ‘there is no afterlife’. They are in Hell because their intellectual thoughts were wrong and they spread them to others.

(2) The following passage occurs in the sixth circle.

Canto XI 22-27 ‘Every evil deed despised in Heaven // has as its end injustice. Each such end // harms someone else through either force or fraud. // ‘But since the vice of fraud is man’s alone, // it more displeases God, and thus the fraudulent // are lower down, assailed by greater pain.

This passage does well to show which ‘evils’ are worse than others. And as Hope and I earlier noted, the ones who committed ‘evils’ that are less bodily and more intellectual in nature are the ones that are sent to worse punishments deeper in the circles of Hell.

(3) The following passage occurs amidst the Wood of the Suicides in the seventh circle; Dante has just unintentionally ripped apart part of the soul of Pietro della Vigna, who has turned into a thorny tree that sheds blood when its branches are snapped.

Canto XIII 37-39 ‘We once were men and now are turned to thorns. // Your hand might well have been more merciful // had we been souls of snakes.’

(4) The following passages depict the appearance of the monster of Fraud.

Canto XVI 129-133 …I swear to you, reader, // that I saw come swimming up // through that dense and murky air a shape // to cause amazement in the stoutest heart, // a shape most like a man’s…

Canto XVII 1-15 [Virgil:] ‘Behold the beast with pointed tail, that leaps // past mountains, shatters walls and weapons! // Behold the one whose stench afllicts the world!’ // And that foul effigy of fraud came forward, // beached its head and chest // but did not draw its tail up on the bank. // It had the features of a righteous man, // benevolent in countenance, // but all the rest of it was serpent. // It had forepaws, hairy to the armpits, // and back and chest and both its flanks // were painted and inscribed with rings and curlicues…

I find it interesting that this monster has “a shape most like a man’s”. As is well-known, some external criticisms of Christian doctrine like to point out the illogical nature of the anthropomorphisms within its doctrine of good; while I am not religious, I do think it plausible that good and evil are conceptualized the way they are, because it is difficult to teach abstract concepts.

Yet if we set this criticism aside and think about how God (or rather, Jesus) and these monsters are portrayed, it is interesting to see that God, or goodness, is depicted as a perfect man and evil monsters are depicted as terribly deformed versions of men.

Also very interesting is that this monster of Fraud is “benevolent in countenance”. It appears good in a certain respect. This may explain why some people are persuaded to do fraudulent things, or mistakenly think that those things are genuinely appealing.

(5) In the following passage Dante shares his horror at the contortion of the souls of false prophets, sorcerors, etc.

Canto XX 13-15, 22-24 Their faces were reversed upon their shoulders // so that they came on walking backward, // since seeing forward was denied them. // …when I saw, up close, our human likeness // so contorted that tears from their eyes // ran down their buttocks, down into the cleft.

(6) The following passage is of Guido da Montefeltro explaining to Dante the sins for which he is stuck in the eighth circle. His sins are most certainly of an intellectual nature as opposed to an indulgence in physical pleasures.

Canto XXVII 74-78 …my deeds were not // a lion’s but the actions of a fox. // ‘Cunning stratagems and covert schemes, // I knew them all, and was so skilled in them // my fame rang out to the far confines of the earth.

(7) The following passage is of Count Ugolino sharing the ‘evil’ that Archbishop Ruggieri did him. Both are in the ninth circle of Hell (Treachery). Ruggieri jailed Ugolino together with his three children.

Canto XXXIII 58-64… 67-74 ‘the sorrow of it made me gnaw my hands. // And they [his children], imagining I was doing this // from hunger, rose at once, saying: // ‘ “Father, we would suffer less // if you would feed on us: you clothe us // in this wretched flesh—now strip it off.” // ‘Then, not to increase their grief, I calmed myself. // …. ‘When we had come as far as the fourth day // my Gaddo threw himself on the ground before me, // crying, “O father, why won’t you help me?” // ‘There he died; and even as you see me now // I watched the other three die, one by one, // on the fifth day and the sixth. And I began, // ‘already blind, to grope over their bodies, // and for two days called to them, though they were dead.

I don’t know about you, but I consider inflicting such pain on another person incomprehensible.

For reasons of time, I stop myself from recording many of my other thoughts on the Inferno. I think the above material is enough to give some plausibility to the thought that in Dante’s Inferno, a work held in high esteem in Christian teaching, an ‘evil’ is of a worse kind when it is of an intellectual nature, without emotions or feelings. These intellectual ‘evils’ are dealt harsher punishment, depicted as inhumane, and thus incomprehensible.

The fact that the pathê-uninvolved kind of sins is considered worse than the pathê-involved kind… suggests that there is at least one distinction that can be drawn among ‘evil’ things: are feelings involved or not? I would suggest, contra my friend, that the common (in at least English) conception of ‘evil’ accommodates this Christian internal divide; and thus, ‘evil’ persons and actions can be categorized according to the criterium: accompanied or not accompanied by ‘hate’.

A quick survey I ran on March 20th – 21st, 2020 on around 20 friends (I admit this is statistically insignificant and discernibly unrigorous) of various cultural backgrounds and native languages (US-American, Norwegian, German, British, Spanish, Canadian, Chinese, Peruvian, Australian, Japanese etc.) supports a general consensus regarding the conceptual availability of this distinction, cross-culturally.

Let me, then, work for the remainder of this entry with the following adjustments to my friend’s idea: there are many kinds of ‘evil’ people and ‘evil’ acts. Some ‘evil’ people and ‘evil’ acts operate accompanied by ‘hate’ and others operate unaccompanied by ‘hate’. The latter is considered, intuitively by many, to be worse than the former, perhaps because of Christian teaching, perhaps other influences. Let us note that this intuition is not shared by everyone, and so let us not rely on it logically. Perhaps also, ‘evil’s that are accompanied by ‘hate’ are generally more relatable to the average non-psychopathic person than ‘evil’s that are not accompanied by ‘hate’. And finally, ‘evil’s that are accompanied by ‘hate’ are generally—at least thought to be—more common than ‘evil’s unaccompanied by ‘hate’.

In the following section, I expand on this understanding of ‘evil’.

Section III: ‘evil’ w/o a side of ‘hate’ and the possibility of thoughtless ‘evil’

In this section, I expand on (3): my friend’s idea on the relationship between ‘evil’ and ‘hate’ immediately struck me as being in stark contrast to my understanding of how most people conceptualize ‘evil’ in the famous phrase, ‘the banality of evil’. I decided to close-read Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, from where the phrase originates. (I’d been meaning to read it for ages.)

To understand the background within which Arendt wrote Eichmann in Jerusalem, I read the Wikipedia page on Adolf Eichmann (and got carried away reading some of its related links) before venturing to read the book.

Eichmann in Jerusalem may well be the best book I have ever read. I have admired Arendt’s work (e.g., see my summary of her essay “The Freedom to be Free”) in the past, but this book left me in awe of how brilliant and fair her mind is. I hope to later write a separate journal entry for the book, but for my present purposes I restrict myself to drawing the following brief observations that strike me as most relevant to my overall thought process:

0) Eichmann committed ‘evil’ actions.

Arendt is, from what I understand, clearly working with the assumption that Adolf Eichmann, who contributed much to the effectiveness and efficiency of the execution of Nazi policies for Jews from 1932-1945, committed ‘evil’ acts. I do believe I agree with her.

This assumption, obviously, does not entail thinking that Eichmann is an ‘evil’ person. In fact, if Arendt were asked to come up with several adjectives to describe Eichmann most essentially, I would guess that ‘evil’ would not be one of them. Instead, she would say ‘stupid’, ‘repetitive’, ‘akratic’, ‘inconsistent’, and ‘low-class’ all before a label like ‘evil’. This entry is not the time or place to do an analysis of the differences between what makes a person ‘evil’ and what makes an act ‘evil’. I leave this for future days, and instead stick to the following core thoughts:

It seems right to me to say that a person with good intentions can mistakenly do something ‘bad’ and a person with bad intentions can unintentionally do something ‘good’, etc…. the point being that the goodness and badness of intentions is conceptually separable from the goodness and badness of an act, though they are not unrelated. The mismatch between the goodness and badness of intentions and acts happens, I would suggest, through one or more of the following primary reasons that immediately come to mind:

- ignorance of certain factors of a particular situation (due to the impossibility of knowing them or to insufficient effort to find them out)

- an insufficient deliberative thought process (due to an inability to think or to insufficient effort to think)

- one’s orientation towards what is right and wrong being out of whack (which could be due to a wide variety and combination of factors)

Similarly, it seems right to me that, through one thing or another, a person with good intentions can, in certain situations, commit ‘evil’ acts. Eichmann’s case seems like that of a person who believes he has good intentions (e.g., “I want to do my job well”) but does an ‘evil’ action (repeatedly) through:

- full knowledge of what his actions would entail [this is supported by great evidence],

- a sufficient deliberative thought process regarding what to do and not do [this judgment is a bit up in the air for me; but if his deliberation for each action he took was insufficient, I think that this fact likely boils down to #3:],

- BUT an orientation towards what is good and bad being, without any effort on my part to exaggerate, very thoroughly out of whack [I suppose this judgment depends on what one thinks about Nazi policies, but I think I am right to say that they were terrible.*]

The third point should remind you of Section II. This is something that, at least in Christian theology, makes you an ‘evil’ person who deserves to go to Hell (e.g., Epicurus and his followers). I suspend judgment on such a claim; I think this point is unnecessary for the purposes of my thoughts today.

If you at this point question with my assumption that many of Eichmann’s actions were ‘evil’, I would suggest reading about everything Eichmann did from 1932-1945, for I have no desire to discuss this claim further. One example of many: he did all he could to speed up the evacuation (and thus execution) of hundreds of thousands of Jews from Budapest to Auschwitz even after Himmler (his superior)’s orders to stop the process. Apparently, he did everything he did without any personal ‘hate’ for Jews.

[*I hope that someday everyone will fully appreciate the severity of what happened under Nazi policies (I believe many people mistakenly think that we are already at this point) and prevent present and future instances of repeating the same events even if there are socio-economic or political costs. I hope this because I think that if everyone fully appreciated the severity of what happened in the past, everyone would feel the ethical compulsion to forcefully criticize other entities that engage in the same actions.

Yet Germany, a country whose members generally pride themselves in the country’s reflection on its past, is currently failing to even meekly criticize entities engaging in similar actions (e.g., the CCP, reference 1, reference 2, reference 3, reference 4, reference 5, reference 6). Germany engages further and further economically and politically with another political entity that seems to be making exactly the same mistakes for which it self-flagellates. This behavior is, at least to me, an indication that for all it’s “effective” post-Third Reich education programs, plenty of Germans and especially plenty of Germans in leadership positions continue to lack the proper orientation towards and appreciation for what is right and wrong.

I have been thinking about this idea and discussing it with a wide variety of my German friends for the past several months. I hope to finish processing my preliminary thoughts regarding the topic in the future through further discussion with both my German and international friends.]

1) Eichmann seems to have committed ‘evil’ actions towards Jews without ‘hate’ for them.

It is not implausible, I think, to think that Eichmann, along with some other Nazi individuals, committed ‘evil’ acts without ‘hate’ for Jews nor for the other victims of Nazi policies. Here, by “without ‘hate'”, I mean ‘without a visceral feeling of desire to hurt Jews, without wanting to see Jews not exist’, as I claimed in the first section is my friend’s understanding of the term.

Having done all he did without ‘hate’ for Jews is indeed the psychological account that Eichmann presented as his own in court. He did, indeed, help his own Jewish relatives evacuate early on in the Third Reich; he did, indeed, have a Jewish mistress during his appointment in Vienna; and he did, indeed, treat with great respect several important Jewish professional contacts with whom he worked very closely to carry out his assignments. Records back these claims.

Here, I would like to introduce the set of actions taken by Rumanian leaders from 1937-1944 to provide contrast to this possible understanding of Eichmann and his psychology. I could be wrong, but I think you will agree with me that the following set of actions is an example of ‘evil’ actions for which it is more than plausible to attribute visceral ‘hate’ for Jews as motivation:

…in Rumania even the S.S. were taken aback, and occasionally frightened, by the horrors of old-fashioned, spontaneous pogroms on a gigantic scale; they [the S.S.] often intervened to save Jews from sheer butchery, so that the killing could be done in what, according to them, was a civilized way. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that Rumania was the most anti-Semitic country in prewar Europe. Even in the nineteenth century, Rumanian anti-Semitism was a well-established fact; in 1878, the great powers had tried to intervene, through the Treaty of Berlin, and to get the Rumanian government to recognize its Jewish inhabitants as Rumanian nationals–though they would have remained second-class citizens. They did not succeed, and at the end of the First World War all Rumanian Jews… were still resident aliens. It took the whole might of the Allies, during the peace-treaty negotiations, to “persuade” the Rumanian government to accept a minority treaty and to grant the Jewish minority citizenship. This concession to world opinion was withdrawn in 1937 and 1938, when, trusting in the power of Hitler Germany, the Rumanians felt they could risk denouncing the minority treaties as an imposition upon their “sovereignty,” and could deprive several hundred thousand Jews, roughly a quarter of the total Jewish population, of their citizenship. Two years later, in August, 1940, some months prior to Rumania’s entry into the war on the side of Hitler Germany, Marshal Ion Antonescu, head of the new Iron Guard dictatorship, declared all Rumanian Jews to be stateless… That same month, he also instituted anti-Jewish legislation that was the severest in Europe, Germany not excluded… Hitler himself was aware that Germany was in danger of being outdone by Rumania, and he complained to Göbbels in August, 1941, a few weeks after he had given the order for the Final Solution, that “a man like Antonescu proceeds in these matters in a far more radical fashion than we have done up to the present.”

…Deportation Rumanian style consisted in herding five thousand people into freight cars and letting them die there of suffocation while the train traveled through the countryside without plan or aim for days on end; a favorite follow-up to these killing operations was to expose the corpses in Jewish butcher shops. Also, the horrors of Rumanian concentration camps, which were established and run by the Rumanians themselves because deportation to the East was not feasible, were more elaborate and more atrocious than anything we know of in Germany. When Eichmann sent the customary adviser on Jewish affairs, Hauptsturmführer Gustav Richter, to Bucharest, Richter reported that Antonescu now wished to ship a hundred and ten thousand Jews into “two forests across the river Bug,” that is, into German-held Russian territory, for liquidation. The Germans were horrified…

…in the middle of August [1942]–by which time the Rumanians had killed close to three hundred thousand of their Jews mostly without any German help–the Foreign Office concluded an agreement with Antonescu “for the evacuation of Jews from Rumania, to be carried out by German units,” and Eichmann began negotiations with the German railroads for enough cars to transport two hundred thousand Jews to the Lublin death camps…

It is a curious fact that Antonescu, from beginning to end, was not more “radical” than the Nazis (as Hitler thought), but simply always a step ahead of German developments. He had been the first to deprive all Jews of nationality, and he had started large-scale massacres openly and unashamedly at a time when the Nazis were still busy trying out their first experiments. He had hit upon the sales idea more than a year before Himmler offered “blood for trucks,” and he ended, as Himmler finally did, by calling the whole thing off as though it had been a joke. (p. 195-198)

It is amazing, I think, in a horrific way, what individuals as well as larger organizations (e.g. Antonescu & Rumania, Hitler & the Nazis) can desire and decide to do when there is individual or collective deep-seated ‘hate’ to motivate actions. Rumania, I think it is rather straightforward to say, very much enjoyed a cammeraderie with Hitler in their “understanding of the Jewish problem”. And this ‘hate’ towards Jews seems to me an important piece of the puzzle for us to understand why the Rumanians did what they did.

As is evident through much of Arendt’s book and other external records, Nazi execution of anti-Semitic policy was impossible to carry out in places that did not share such ‘hate’ towards Jews–places that, in Nazi internal reports, did not share “an understanding of the Jewish problem”. The stories from Bulgaria are particularly fascinating, where the government leaders and its citizens actively dispersed Jews instead of concentrating them, prevented Jews from going to the train stations, demonstrated in protest to the anti-Jewish legislation enacted under great pressure from Nazi authorities, and where, finally, German officers stationed there became “unreliable” in the eyes of the Nazis to carry out their assignments… “unreliable” because those officers could no longer understand why murdering Jews was a good idea. The records of what happened in Bulgaria seems to be the best version of that which happened elsewhere where ‘hate’ for Jews was lacking (e.g. Denmark, Italy).

From the wide spectrum of cases (from Bulgaria and Denmark all the way to Rumania) all technically under Nazi rule, it is clear, Arendt argues and as I have been convinced, that whether or not there was a general underlying consensus among the individuals of a society to ‘hate’ Jews was immensely relevant in determining whether or not that society would cause Jews harm… whether or not individuals in that particular society found it appropriate, and in certain cases right, to cause them harm.

Now, it is still possible that a certain number of German, Polish, Austrian, Czech, Hungarian, etc. official-individuals who actively participated in the execution of the Final Solution (which required the cooperation of more than a million individuals) had no personal ‘hate’ towards Jews and acted solely out of their feelings of duty or their feeling the need to blend in, protect their own lives. Basically everyone involved in the Final Solution, who didn’t kill themselves before they were captured and we could ask them for their motivations ourselves, claimed such an “inward opposition” after the war. For example, “Dr. Otto Bradfisch, former member of one of the Einsatzgruppen, who presided over the killing of at least fifteen thousand people, told a German court that he had always been ‘inwardly opposed’ to what he was doing.” That he did all he did to not blow his cover as a non-anti-Semite. Arendt retorts: “Perhaps the death of fifteen thousand people was necessary to provide him with an alibi in the eyes of “true Nazis.”.” (p. 139).

I think to estimate that this certain number comprised a large portion of the total members would be an extremely charitable way to understand them, to say the least. Arendt cites:

In the Nuremberg documents “not a single case could be traced in which an S.S. member had suffered the death penalty because of a refusal to take part in an execution” [Herbert Jäger, “Betrachtungen zum Eichmann Prozess,” in Kriminologie and Strafrechtsreform, 1962]. And in the trial itself, there was the testimony of a witness for the defense, von dem Bach-Zelewski, who declared: “It was possible to evade a commission by an application for transfer. To be sure, in individual cases, one had to be prepared for a certain disciplinary punishment. A danger to one’s life, however, was not at all involved.” p. 106-7

No members, at least, of the privileged class of officers (the S.S., for example, comprised of approximately 800,000 volunteers) had any real threat to their own lives. It seems to me more accurately described to say that they, of their own will, engaged in supporting the aims of the Holocaust. And it is difficult to understand how these individuals caused this harm and suffering without ascribing to them ‘hate’ for their victims. I think this especially in light of the countable number of accounts we have of people who, despite being unprotected (unlike, for example, Eichmann, lieutenant colonel of the S.S.), refused to take part in aiding the Nazis or even actively sabotaged Nazi plans (p.138).

Yet Eichmann’s testimony during his trial, as well as the records available on Eichmann’s words, actions, and relationships prior to 1945 still seem to support his adamant denial of hating Jews. Could he be an example of the small minority of individuals to actively participated in the Final Solution without any ‘hate’ towards Jews? Arguing for this is outside the scope of this journal entry; I refer you to read available external sources and analyses of his life and testimony. If so, his case is interesting, because the cause of Eichmann committing ‘evil’ acts is traced elsewhere, and this cause would shed light on how I understand my primary topic, the colloquial use of the term ‘hate’.

And, even if I am wrong in my preliminary assessment of Eichmann, which I am happy to be, I still want to conceptually entertain this interpretation of his psychology for the remainder of this section. Let us mull over this archetype that Eichmann so consistently displayed in his trial: the one who commits ‘evil’ acts without feeling ‘hate’ towards those whom he commits that said ‘evil’, without any feeling of desire to harm them.

A preliminary: his insistence throughout the trial in Jerusalem that he did not have any personal animosity towards Jews (with some cracks) is further augmented by his even more consistent denial of ever having killed a Jew (though he had a large hand in maximizing the murder of millions of Jews):

“I never killed a Jew or, for that matter, I never killed a non-Jew…. I never gave an order to kill a Jew nor an order to kill a non-Jew.” p. 218

More interesting: Eichmann, bafflingly, exhibited no recognition at any point in time that he ever committed any morally reprehensible act. This is not an interpretation; this is factual. Never once in his trial nor in his dying breath before his hanging in 1962 did Eichmann admit wrong doing. His dying breath hailed back to his love of Germany, Austria, and finally of Argentina where he hid until his abduction. Interviewed years later, his son made a statement expressing that he thought it best or at least appropriate that his father was hung, because it was not only in court (where he would have had legal incentive to deny wrong doing) but also in his private life that he denied any feelings or remorse or regret for his part in the Final Solution.

Eichmann’s self-conception is interesting in many ways with regards to many things, but what I find most interesting is the following: Eichmann thinks of himself as having a strong commitment to act according to what he thinks is good and bad, and he believes that he never did anything that violated his own conscience. The following passage illustrates this claim and is also my primary reason to think that Eichmann acted with what I earlier called a sufficient deliberative thought process; Arendt describes him in the trial:

“The first indication of Eichmann’s vague notion that there was more involved in this whole business than the question of the soldier’s carrying out orders that are clearly criminal in nature and intent appeared… he suddenly declared with great emphasis that he had lived his whole life according to Kant’s moral precepts, and especially according to a Kantian definition of duty. This was outrageous, on the face of it, and also incomprehensible, since Kant’s moral philosophy is so closely bound up with man’s faculty of judgment, which rules out blind obedience….

…to the surprise of everybody, Eichmann came up with an approximately correct definition of the categorical imperative: “I meant by my remark about Kant that the principle of my will must always be such that it can become the principle of general laws”…. He then proceeded to explain that from the moment he was charged with carrying out the Final Solution he had ceased to live according to Kantian principles, that he had known it, and that he had consoled himself with the thought that he no longer “was master of his own deeds,” that he was unable “to change anything.” What he failed to point out in court was that in this “period of crimes legalized by the state,” as he himself now called it, he had not simply dismissed the Kantian formula as no longer applicable, he had distorted it to read: Act as if the principle of your actions were the same as that of the legislator or of the law of the land – or, in Hans Frank’s formulation of “the categorical imperative in the Third Reich,” which Eichmann might have known: “Act in such a way that the Führer, if he knew your action, would approve it” (Die Technik des Staates, 1942, pp. 15-16). Kant, to be sure, had never intended to say anything of the sort; on the contrary, to him every man was a legislator the moment he started to act: by using his “practical reason” man found the principles that could and should be the principles of law. But it is true that Eichmann’s unconscious distortion agrees with what he himself called the version of Kant “for the household use of the little man.” In this household use, all that is left of Kant’s spirit is the demand that a man do more than obey the law, that he go beyond the mere call of obedience and identify his own will with the principle behind the law – the source from which the law sprang. In Kant’s philosophy, that source was practical reason; in Eichmann’s household use of him, it was the will of the Führer. (p.146-7)

That Eichmann’s moral code over time adhered to whatever was the will of the Führer seems to me correct. The case I earlier mentioned, namely, his refusal to accept and even to try to sabotage Himmler’s order to stop working on the Final Solution does well to support this claim (as do many of his other actions for which I do not have space to expand). He knew that Himmler’s orders ran in opposition to the Führer’s order, and thus to obey Himmler’s last orders and, incidentally, to do the objectively right thing: to stop killing people, ran against his conscience… and thus, he did not obey them; he kept sending Jews to their death until the very end of the war.

Eichmann’s moral compass had, over time, become oriented in a way that was very thoroughly distorted from what is right and wrong, good and bad. And this, I suggest, is the reason Eichmann never admitted wrong doing. He never personally recognized the fact that he ever did anything for which he should be sorry. His orientation towards what is good and bad being very thoroughly out of whack is, or so I suggest, that which explains his total lack of the approriate emotional response that is in fact warranted by a non-psychopathic individual (which he otherwise seemed very much to be) that commits acts like that which he did.

I wonder what others’ intuitions are regarding Eichmann’s moral responsibility (assuming he did not act out of ‘hate’) in comparison to those who did act out of ‘hate’ (e.g., a leading member of the Rumanian effort). Both seem to me to have had more or less the same causal responsibility of the suffering of an absurd number of Jews.

I find it interesting that my immediate emotional reaction to what I read about the Rumanians (not only in Arendt’s book but also in other sources) is horror, but my immediate emotional reaction to Eichmann is intense disappointment. That someone so idiotic, so blind, so utterly lame was put in such a position of influence and did such a good job expediting the suffering of so many faultless people makes me feel despair for the efforts of so many good people working hard to make the world better.

2) Repeatedly and thoughtlessly engaging in any activity seems… bad.

Given that Eichmann’s orientation towards what is good and bad being out of whack is a plausible and likely significant contributor to his behaving as he did and to his not feeling bad for behaving as he did, I think the next thing to wonder is the following: how was it possible for Eichmann’s orientation towards what is good and bad to become so distorted?

Now, at the Nürnberg trials, in Arendt’s analysis of Eichmann, in popular culture, and most obviously in the famous Milgram experiment conducted at Yale in 1961 (the experiment designed specifically to answer the question “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders?”), etc. there is an oft-repeated account for how a person without desire to harm anyone may become ‘stuck’ in a situation where they feel the need to obey orders from a person of authority; in Eichmann’s case, Hitler. It is true that the reverence for Hitler’s authority seems particularly potent in him:

“Hitler, [Eichmann] said, “may have been wrong all down the line, but one thing is beyond dispute: the man was able to work his way up from lance corporal in the German Army to Führer of a people of almost eighty million…. His success alone proved to me that I should subordinate myself to this man.” His conscience was indeed set at rest when he saw the zeal and eagerness with which “good society” everywhere reacted as he did. He did not need to “close his ears to the voice of conscience,” as the judgment has it, not because he had none, but because his conscience spoke with a “respectable voice,” with the voice of respectable society around him.”

This piece of the puzzle that is Eichmann’s mind is covered well in the literature, so I’d like to set this point aside and focus instead on a point that those who know me well will immediately recognize as inspired by my favorite philosopher. 😉

In order to set this point up, I note two background assumptions. The first is shakier than the second, for it draws primarily from my personal experience: there seems to be in at least some people a natural desire (or dare I say, a need) to conceptualize themselves as a good, or at least decent, person. My evidence for this claim is mainly anecdotal, but some psychological studies support this as well. There is, of course, the cultural archetype of the “nice guy”, who is a generalization of the sorts of people who think themselves a nice person and feels misunderstood when other people call them an asshole.

The second is supported by many experiments: there seems to be a natural and powerful mechanism operating subconsciously in people’s minds: rationalization. I refer you most directly to split-brain experiments where the right brain is exposed to certain stimuli and reacts to it. The left brain that is exposed to only the behavior caused by the stimuli of which it is unaware somehow always verbalizes plausible but entirely unrelated reasons for the behavior. Basically, our rationalization game: strong.

These two assumptions together create a dangerous combination where many people, under most circumstances wherein they take action, rationalize or come up with bull-shit reasons for what they did… reasons that work to maintain their own self-conception as a good, or at least decent, person.

I now feel comfortable revealing my Aristotelian spirit. My proposed piece of the puzzle is interesting, I think, because it goes one step further than the Milgram experiment to understand what we can understand of Eichmann through his testimony, for the Milgram experiment and Eichmann’s admiration for Hitler can only go so far as to explain why he did what he did, obeying Hitler’s orders. What is left unexplained is why he (and many other Nazis’) did not feel bad for doing what he did, even 15 years after the war during his trial in 1962. I think this is particularly interesting, because it was manifest in trial records that Eichmann understood that the international community thought he did something wrong, but he did not seem to understand that he actually did do anything wrong; he never expressed feelings of guilt. How did his conscience shift from 1932 when he joined the Nazi party to 1944-5 when he was frantically speeding up deportations to Auschwitz and ridding as many Jews as possible?

My line of thought takes a hint from many records of Eichmann throughout the years in which he participated in Nazi efforts. His start, I think, is quite telling:

“Kaltenbrunner had said to him: Why not join the S.S.? And he had replied, Why not? That was how it had happened, and that was about all there was to it.” (p. 53)

This thoughtless (honestly pathetic) entry into the Nazi party that was to be the start of Eichmann’s thirteen-year successful career, I think, says a lot about his thought process or lack thereof for his own actions. He had no good reason to join the party other than his lack of a good job; he hadn’t known what the party’s platform was, had never read Mein Kampf, had never personally hated Jews, etc. Without any positive reason to join the Nazis, Eichmann joined.

And, he never thought up another idea for himself; he stuck to it, carried by momentum. He moved up among the ranks of the Nazis very successfully since he obediently and fully followed the orders or those above him without question. Given a particular task, he carried it out as best as he could, and he repeated this endeavor over and over again. By the time the Wannsee Conference was held in January 1942, Eichmann had spent a decade thoughtlessly repeating, over and over again getting used to operating under the law of the land, which incidentally was Hitler’s word.

Through his own unquestioning, thoughtless, and repetitive execution of actions over a prolonged length of time, Eichmann’s orientation towards what is good and bad became distorted, shifted by heavy rationalization for his actions so that he could maintain his own ‘good person’ self-conception, a self-conception he kept until his hanging. Thoughtlessly and repetitively engaging in wrong activity eventually made Eichmann’s understanding of right and wrong align with that activity. Thoughtlessly and repetitively engaging in an activity eventually made that activity even feel right for Eichmann. This is what I suggest.

Eichmann had many opportunities, or so I think, to decide not to do what he did. Every single moment of every single day from 1932 all the way to 1945, he had the opportunity to think and to realize that he was engaging in morally problematic behavior. As we know very well with conviction, he, an early and important member of the Nazi party, never had any threat to his own life to stop contributing to mass genocide and start anew with other work. But he did not take any of these opportunities. He chose in his long and comfortable career to not take a single one of these moments, these opportunities to think; for not meeting this basic requirement for a self-directed human life, he is guilty. And, it seems right to me to categorize his type of ‘evil’ actions, this ‘hate’-less utterly pathetic type of ‘evil’, as the thoughtless kind.

Due to the richness of Arendt’s thoughts, there are infinitely more topics that I want to think about, but for reasons of time, I press pause on writing further. I’d recommend to anyone to read her book, especially the Epilogue which is particularly inspiring.

Note: Thank you to my friend Lisha Ruan, with whom I had a lovely 1.5 hour phone call early on in my thought process displayed throughout this post, but most interestingly on the hypothetical scenarios regarding Adolf Eichmann’s psychology.

Section IV: ‘hate’ as a term, connection to my immediate thoughts on ‘evil’

In this final section, I return to the original topic–the use of ‘hate’ in colloquial speech–and incorporate my finally-a-little-more-than-zero-understanding of ‘evil’ and ‘hate’ into whether or not I want to continue to use ‘hate’ in my regular vocabulary.

1) Separate from that which is discussed in sections II & III, the first thing I thought about is whether there are words towards which I have a similarly negative reaction as that of my friend’s towards ‘hate’. In the past I had such negative feelings when people used the term ‘cunt’; I still have a harsh negative reaction towards the n-word when used outside the bounds of rap music.

My negative reaction to the term ‘cunt’, however, has completely vanished in the past year and a half upon making close Australian friends. The meaning behind their use of the term seems to me entirely unproblematic in stark contrast to how it is used in the U.S. I still don’t say it myself, but if they say it I am no longer troubled. Thus, if the meaning behind someone’s use of ‘hate’ is not problematic in some way, then, ceteris paribus, I would not find it problematic for them to use it.

The n-word has historical, political and sociological complications (reasons against using the term) far beyond what any plebian conceptual analysis confined to language could offer or justify to individuals not of African descent; I will never utter it (outside of rapping, which is obviously one of my major pasttimes). Could ‘hate’ something like the this? I tried this hypothesis, but, no, I do not think so; ‘hate’ in it of itself seems to me in no way similarly problematic.

2) When I looked it up, I found that there are many more synonyms to ‘hate’ than I would have expected. Let me name a few: abhorrence, detestation, loathing, despising, enmity, disgust, revulsion, repugnance…. I found that several of these gave me a nasty feeling just dwelling on the meanings they carry. What relationship does each have with ‘hate’?

I am happy to be wrong (and really I may come back to revise this part of this journal after consulting some of my linguist friends), but it was my impression while thinking about this question that all of these words, including the few that caused me distress, fall under the umbrella of ‘hate’. ‘Hate’ is in one sense weaker (less specified) but in a sense much stronger: all the feelings involved in these other terms together combined is still accurately an instance of ‘hate’. Thinking thus, it seemed to me that my friend’s understanding of ‘hate’ likely involves being near that extreme, where all of these terms could well be applicable. Very extreme, indeed.

There are a few other people I have encountered in my life the last twenty-four years who have expressed to me similar qualms with the term. It is not, however, my own personal understanding of the English term that it is at the extreme of the spectrum, encompassing all of these synonymous terms’ meanings.

And, I thought, even if ‘hate’ objectively is the extreme of negative feelings (which it is not at all clear to me that this is right) and thus has a terrible meaning behind it, I would be concerned to create a new form of a euphemism treadmill for the language I use in my thoughts.

The idea of the euphemism treadmill, presented by neuroscientist Steven Pinker in his book The Blank Slate (2002), is something like the following: a linguistic pattern wherein terms that are introduced to replace a problematic word (usually by causing others offense) eventually become problematic themselves like the terms they replaced.

The paradigmatic example is the set of terms used to refer to people with mental disabilities. The treadmill starts at the end of the 19th century with a replacement of the previously offensive terms ‘feeble-minded’ and ‘idiotic’ with ‘retarded’ as the clinical term. ‘Retarded’ later became offensive and thus was replaced with ‘mentally challenged’ with variations. Right now I think we say ‘mental disabilities’, but it is hard to keep track; I will later check with my friend Ainsley (logician), for they keep up with these matters.

It seems to me possible that if I say, “‘hate’ is such a harsh word, let me replace it with another word in my usual speech”, then the other word would begin to carry with it a darker and deeper meaning I and those around me attribute to it… eventually (a Nov 2022 addition: words seem to carry as much weight to them as we give them; thank you to Tobias for helping me shape my thoughts on this topic through countless conversations regarding the power of words to cause offence). This, however, sounds to me like a slippery slope argument on which I do not generally like to rely. On the other hand, I don’t think that this train of thought provides a positive reason in favor of changing my speech patterns. And I strongly refuse to condone the use of “why not X (e.g. change my speech patterns)?” as some sort of justification to X. Doing so would be, as we saw, as thoughtless as Eichmann’s reason to join the Nazi party.

3) Despite finding the above considerations insufficient, I see one good, positive reason for me to change the way in which I use ‘hate’ in my regular speech: I find my own particular use of ‘hate’ problematic. Why? Here is where I think my thoughts on ‘evil’ discussed above may play a clarifying role.

Most primary is the fact that it is simply not true that “I hate myself” or ‘hate’ many of the things that I repeatedly and thoughtlessly say I do. Engaging in (speech) acts that are blatantly not true, strikes me as problematic about my use of ‘hate’ (see also, Harry Frankfurt’s famous essay “On Bullshit” or my summary of it). It is simply not true that I have ever felt ‘hate’ towards something or someone in a significant way. Yet I have thoughtlessly and countless times uttered the term without intending to communicate the meaning that it is supposed to carry.

Further, it seems to me right to think that engaging thoughtlessly and repeatedly in action is generally bad. Doing so somehow makes the agent passively align their judgments with the attitudes the action displays. We saw this in Eichmann: his repeated and thoughtless engagement in terrible acts—that any onlooker could easily have told him was bad—over time, psychologically blinded him from how terrible they were. Eventually, the objective wrongness of his actions had no power to make him feel bad for his doing them. While the wrongness of ‘making a false claim about the extent of one’s own dislike towards something’ is incomparable to the wrongness of ‘contributing to genocide’, the description of ‘thoughtlessly and repeatedly engaging in X to the point where X feels unproblematic’ fits both. My use of ‘hate’ strikes me as something that contributes to the proliferation of false claims, something I do not condone, and it seems possible that my lack of a negative reaction to it is due to my having gotten accustomed to its use by me and others. Once aware of thoughtless behavior with potentially negative ramifications, I should counteract it.

It seems to me an accurate description of what I understand of the world that many people, including myself, do not put sufficient thought into what they say and do before they say or do it. Part of the reason why there is so much miscommunication and many inaccuracies in general is that the vast majority of people do not invest the mental energy it takes to be accurate to reality, and this, in a weak, pathetic, really banal sense, contributes to a lack of truth and goodness in word and action. I would suggest that it is perhaps too widespread of a phenomenon for it to be entirely harmless and that each person in a thoughtless way contributes to whatever harm there is from this phenomenon.

In the rush of enjoying my life, trying to express all it is that I feel or think, do everything that I can do… I am aware of the fact that I must have many bad habits. While I haven’t figured all of them out yet, one of these habits is to do things without sufficient thought. One subset of this, I think, is my failure to choose my words as carefully as I ought to. This exploration of ‘hate’ and ‘evil’ allows me to diagnose this failure in myself today. It is true, I think, that many otherwise thoughtful people around me share in this and other similar bad habits; however, the fact that others do not sufficiently think about nor find the use of ‘hate’ unproblematic is no reason for me to continue proliferating inaccurate terminology from my own mouth. I thus think that my inaccurate-to-reality use of the term ‘hate’ is something worth my effort to change.

I find it highly plausible that there will be times in the future when I do ‘hate’ something or someone. When that happens, there will be a positive reason to use the term, namely, that ‘hate’ is the objectively appropriate term to use in that situation, in virtue of it being true. At that time, I can use it intentionally.

It seems perhaps further worthwhile to be more careful not only with ‘hate’ but with other terms, to speak more precisely, more truthfully and to orient my speech and behavior towards what is good. My friend Lisha asked me the other day, “what do you think about ‘love’?” It seems to me, I told her, that having love in abundance is something that doesn’t cause problems the way that having hate in abundance does… more love can go around more, no? But maybe it is similarly bad to say ‘love’ when you don’t feel it, but it seems good for people to feel it more… is that right? Alas, this is for another day.

While I feel certain that there will be times that I slip up, I hope that I may cease to contribute to thoughtless kinds of ‘evil’, something which is in my power to do. I feel compelled to inculcate the correct orientation to pursue what is good in all my actions, including my speech. I hope I may over time and with further reflection shape well my orientation towards right and wrong.

With that, I shall now return to my more primary interests (in induction, ἐπαγώγη, in Aristotle) and call it a day for this journal entry.

[Thank you also to many of my close friends who have read and commented on, in some way shape or form, this sketch of thoughts for me. These friends include but are not limited to: Merrick Anderson, Luise Betz, Adrian Bösl, Marife Caparo, Sigurd Opdal Eidem, Hope Kean, Joaquin Longares, Adrian Kristing Ommundsen, Ainsley Pullen, Naïs Rachas, Lisha Ruan.]

Bibliography

- Alighieri, Dante, et al. Inferno. Random House, 2003.

- Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Viking Press, 1963.

- Aristóteles. Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Edited by I. Bywater, E Typographeo Clarendoniano, 1986.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, 2017.

- Frankfurt, Harry G. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Pinker, Steven. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Penguin, 2002.

- Plato. Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper, Hackett, 2009.

- Rosen, Gideon. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. volume 103. chapters 1, 4. 2003.

- Williams, Bernard. Moral Luck: Philosophical Papers. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993.

- And other various lectures that I have attended in the last six years of my life.

Books I would like to closely (re/)read:

- Beyond Good & Evil (1886) by Nietzsche

- On the Genealogy of Morals (1887) by Nietzsche

- The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil (2007) by Philip Zimbardo (of the Stanford prison experiment)

- Answer to Job (1952) by Carl Jung

- Ethics Demonstrated in Geometrical Order (1677, posthumous) by Spinoza

- Side note: Reread Euclid’s Elements at some point 🙂

- The Abolition of Man (1943) by C.S. Lewis

- The Road Less Traveled (1978) by M. Scott Peck