Melanie Berman (@melaniesop) and I (@masako.toyoda) hope that recent discourse surrounding Black Lives Matter could benefit from this distinction, so we combined what Professor Simon Gikandi (Princeton University) taught Melanie in a course on modern evil and my familiarity with Arendt’s works to present this idea.

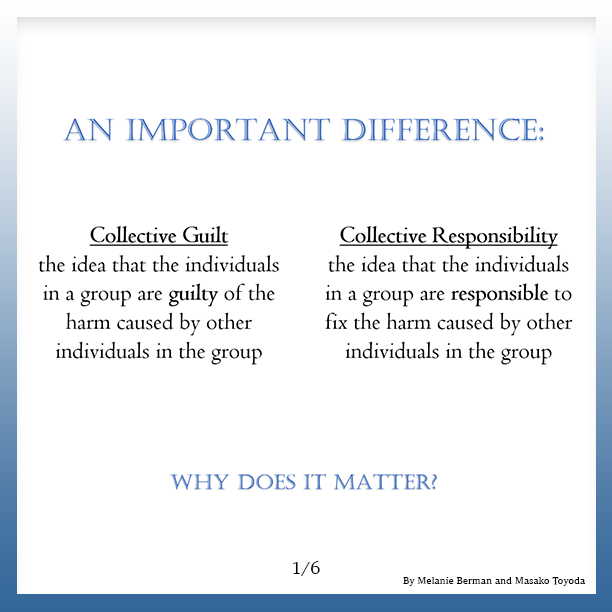

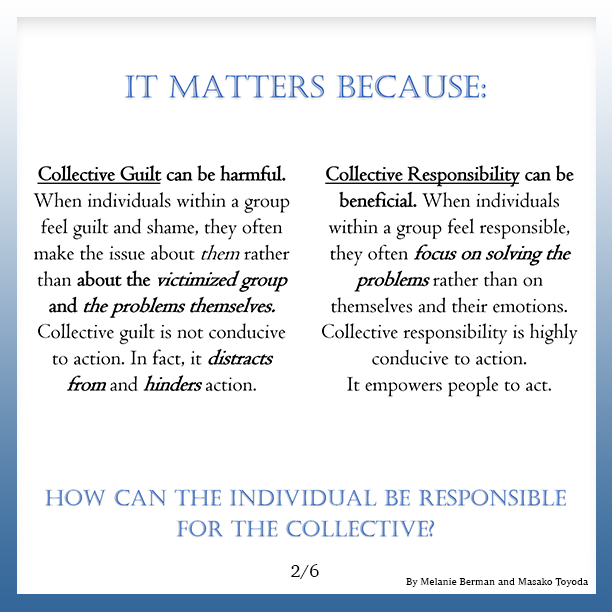

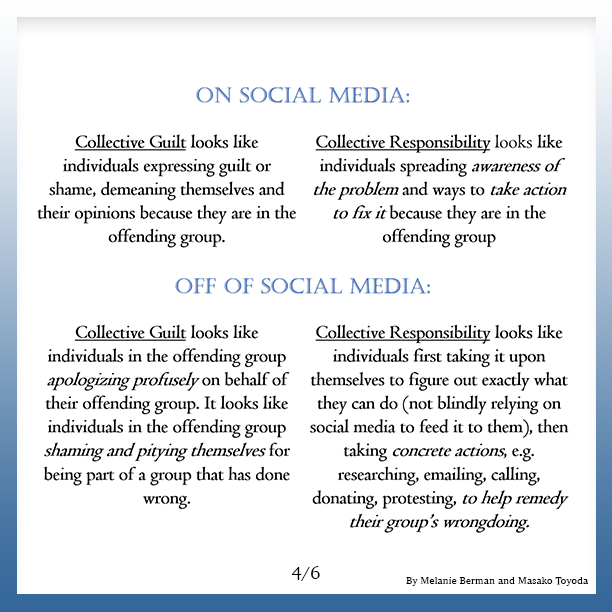

Collective Guilt vs. Collective Responsibility.

This point is “worth making loudly and clearly at a moment when so many good white liberals confess to guilt-feelings with respect to [racism towards blacks]…. in post-War Germany, where similar problems arose with respect to what had been done by the Hitler regime to Jews, the cry ‘We are all guilty’ that at first hearing sounded so very noble and tempting has actually only served to exculpate to a considerable degree those who actually were guilty. Where all are guilty, nobody is.”, Hannah Arendt, a Jew who fled from the Third Reich after being arrested in the 1930’s, wrote decades ago.

For more on collective responsibility:

Hannah Arendt’s amazing, amazing essay “Collective Responsibility” (1987).

For forward-looking collective responsibility:

Collective Responsibility on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which a sort of Wikipedia page for important ideas!

Want to read more? 🙂

Collective Responsibility: Five Decades of Debate in Theoretical and Applied Ethics edited by Larry May, Stacey Hoffmann

Excerpts from Arendt's paper, presented in chronological order:

Page 1: “There is such a thing as resonsibility for things one has not done; one can be held liable for them. But there is no such thing as being or feeling guilty for things that happened without oneself actively participating in them. This is an important point, worth making loudly and clearly at a moment when so many good white liberals confess to guilt feelings with respect to the Negro question. I don’t know how many precedents there are in history for such misplaced feelings, but I do know that in post-War Germany, where similar problems arose with respect to what had been done by the Hitler regime to Jews, the cry ‘We are all guilty’ that at first feeling sounded so very noble and tempting has actually only served to exculpate to a considerable degree those who actually were guilty. Where all are guilty, nobody is.”

“Since sentiments of guilt, mens rea or bad conscience, the awareness of wrong doing, play such an important role in our legal and moral judgement, it may be wise to refrain from such metaphorical statements which, when taken literally, can only lead into a phony sentimentality in which all real issues are obscured.”

Fine-grained but important conceptual distinctions:

“No collective responsibility is involved in the case of the thousand experienced swimmers, lolling at a public beach and letting a man drown in the sea without coming to his help, because they were no collectivity to begin with; no collective responsibility is involved in the case of conspiracy to rob a bank, because here the fault is not vicarious; what is involved are various degrees of guilt. And if, as in the case of the post-bellum Southern social system, only the “alienated residents” or the “outcasts” are innocent, we have again a clear-cut case of guilt; for all the others have indeed done something which is by no means “vicarious.””

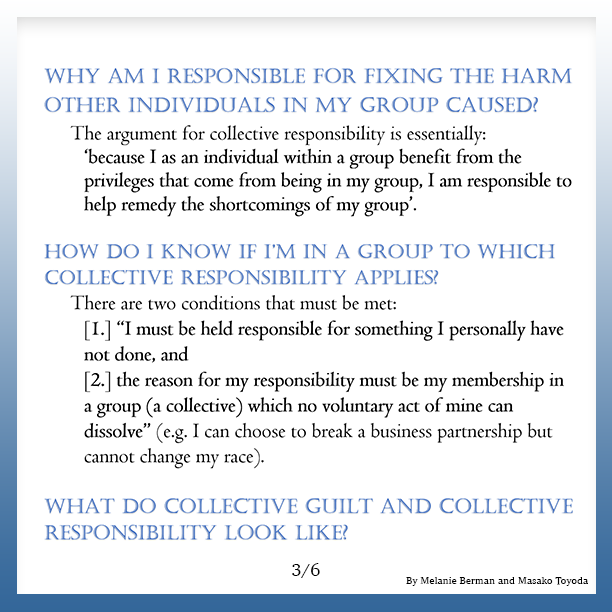

“Two conditions have to be present for collective responsibility: I must be held responsible for something I have not done, and the reason for my responsibility must be my membership in a group (a collective) which no voluntary act of mine can dissolve, that is, a membership which is utterly unlike a business partnership which I can dissolve at will.”

“When Napoleon Bonaparte became the ruler of France, he said: I assume responsibility for everything France has done from the times of Charlemagne to the terror of Robespierre. In other words, he said, all this was done in my name to the extent that I am a member of this nation and the representative of this body politic.

In this sense, we are always held responsible for the sins of our fathers as we reap the rewards of their merits; but we are of course not guilty of their misdeeds, either morally or legally, nor can we ascribe their deeds to our own merits.”

“What I am driving at here is a sharper dividing line between political (collective) responsibility, on one side, and moral and/or legal (personal) guilt, on the other, and what I have chiefly in mind are those frequent cases in which moral and political considerations and moral and political standards of conduct come into conflict. The main difficulty in discussing these matters seems to lie in the very disturbing ambiguity of the words we use in discussions of these issues, to wit, morality or ethics.”

“The question [in morality or ethics] is never whether an individual is good but whether his conduct is good for the world he lives in. In the center of interest is the world and not the self.” Arendt asserts this but with the exception of the Socratic proposition of “It is better to suffer wrong than to do wrong.”

Arendt has an insightful discussion of the history of religion and morality. “My point… is that morality owes this high position in our hierarchy of ‘values’ to its religious origin…. It is more than doubtful that these originally religiously rooted rules of conduct can survive the loss of faith in their origin, and, especially, the loss of transcendent sanctions. (John Adams, in a strangely prophetic way, predicted that this loss would ‘make murder as indifferent as shooting plover, and the extermination of the Rohilla nation as innocent as the swallowing of mites on a morsel of cheese.”) As far as I can see, there are but two of the Ten Commandments to which we still feel morally bound, the “Thou shalt not kill” and the “Thou shalt not bear false witness”; and these two have recently been quite successfully challenged by Hitler and Stalin respectively.”

In discussing the Socratic proposition and the Kantian non-religious and non-political moral prescription… “The even deeper trouble with the argument is that it is applicable only to people who are used to live explicitly also with themselves, which is only another way of saying that its validity will be plausible only to men who have a conscience…. No objective sign of social or educational standing can assure its presence or absence.”

“This vicarious responsibility for things we have not done, this taking upon ourselves the consequences for things we are entirely innocent of, is the price we pay for the fact that we live our lives not by ourselves but among our fellowmen, and that the faculty of action, which, after all, is the political faculty par excellence, can be actualized only in one of the many and manifold forms of human community.”